Advent Series: Death

The first part in an Advent series on the “Four Last Things”

We all know what we’re getting for Christmas.

Not that Santa doesn't have one or two surprises up his big red sleeves. What I mean is that Christmas will probably go, more or less, the way we expect it to. We’ll get up on Sunday morning, have that cup of coffee. Kids everywhere wait impatiently to unwrap the packages under the tree, and reach down to find out what is hiding all the way down in the toe of their Christmas stocking.

Then of course to Church for Christmas Day service, then back home for a nice dinner with relatives and friends.

Yes, with Christmas, we all know what we’re getting.

And in terms of the meaning of Christmas, the reason for the season, we all know about that, too. We come to church fully anticipating to hear about the Baby in the manger, with his Blessed Mother, and so on. Good money says that “Silent Night” and “Hark, the herald angels sing” will be on the rotation. Yes, we all know what we’re getting for Christmas, and, for most of us, whatever else is the matter in our lives, we look forward to Christmas for the comfort and joy that brightens and warms our lives in this otherwise cold and dark time of the year. We need Christmas, not only for these things, but also for Who it reminds us of: Jesus, who became man for our sake, because of his great love for us. Christmas is about God coming to be with us.

With Advent, on the other hand, it’s a lot easier to be uncertain about what we’re getting. By now the Jingolator on the radio is already turned up to 11, Mariah Carey is belting out what she wants for Christmas in the shopping malls, everything is lights, greenery, and peppermint.

Advent is… a little different. In church, our Advent meditations and practices strike a “blue” note in the otherwise nostalgic tones and major key of the commercial ho-ho-holiday season. What time is it?

While the advent of the Messiah is indeed “tidings of comfort and joy,” the voices we hear in Advent—the prophets, John the Baptist, the apostles Paul and James, and Jesus himself—urge us to ‘wake up,’ ‘be on the lookout,’ and to avoid sleeping or drunkenness, because the Messiah, the Anointed One, is coming, and we want to be ready when he arrives. For the rest of our culture, this may be a season for beating the winter blues through indulgence, shopping, holiday parties. But we are exhorted to sobriety, self-control, alertness, as we await the hope to which we are called.

In essence, we must seek now to become the kind of people who, when He comes, will recognize him and welcome his coming; who will see his advent as the fulfillment of our dearest hopes, and not as an interruption to our already comfortable and fulfilled way of life.

That day will come when no one expects it. As Jesus said, the signs of the end times are at hand. But on the other hand, it will be completely unexpected. “No man knows,” Jesus said. “The Son of Man is coming at an unexpected hour.” Just as the flood came without warning and put an end to the world as its inhabitants knew it, so it will be when Jesus comes. The unwary and unprepared will be taken by the calamity, and only those who are awake, alert, and attentive to God—like Noah—will remain.

It sounds as if we are talking about the apocalypse, the end of the world, and in a way we are. Just as no one knows the day or the hour of Jesus’s return, likewise no man knows the day or the hour of his own death.

Jesus Christ will come again in glory on the last day, whenever that will be. But, most likely, all of us will meet him sooner than that, on our last day. Our span of life on earth, which we ourselves cannot know, will end, and we will stand before God.

And yet, death seems, despite all evidence to the contrary, distant from us and from our experience. Richard Challoner wrote in 1801, “the greater part of men, who, though they daily see some or other of their friends, acquaintance, or neighbours carried off by death, and that very often in the vigour of their youth, very often by sudden death, yet always imagine death to be at a distance from them.”

How much more so does our present-day culture represses its awareness of death: hiding it away in hospitals and funeral parlors, obscuring it under medical terminology; trivializing it in the portrayals of violent death to which all of us who watch films and television are to some degree desensitized; avoiding the mention of death through euphemisms, as when we call a funeral a “celebration of life” or speak of a person’s death in sentimental but inappropriate terms—“Heaven has another angel,” etc. Though we think of ourselves as living in a society that has gotten beyond most taboos, death is a big one for us, more so than in most other cultures throughout history.

And this does us no favors, because if we cannot acknowledge the reality of death for each of us, we cannot properly prepare ourselves for death and what comes after death.

The Church likewise, in her cultural captivity, cannot adequately express the hope that we have in the face of death, which we find in the person, and work, and present reign, and future appearing, of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.

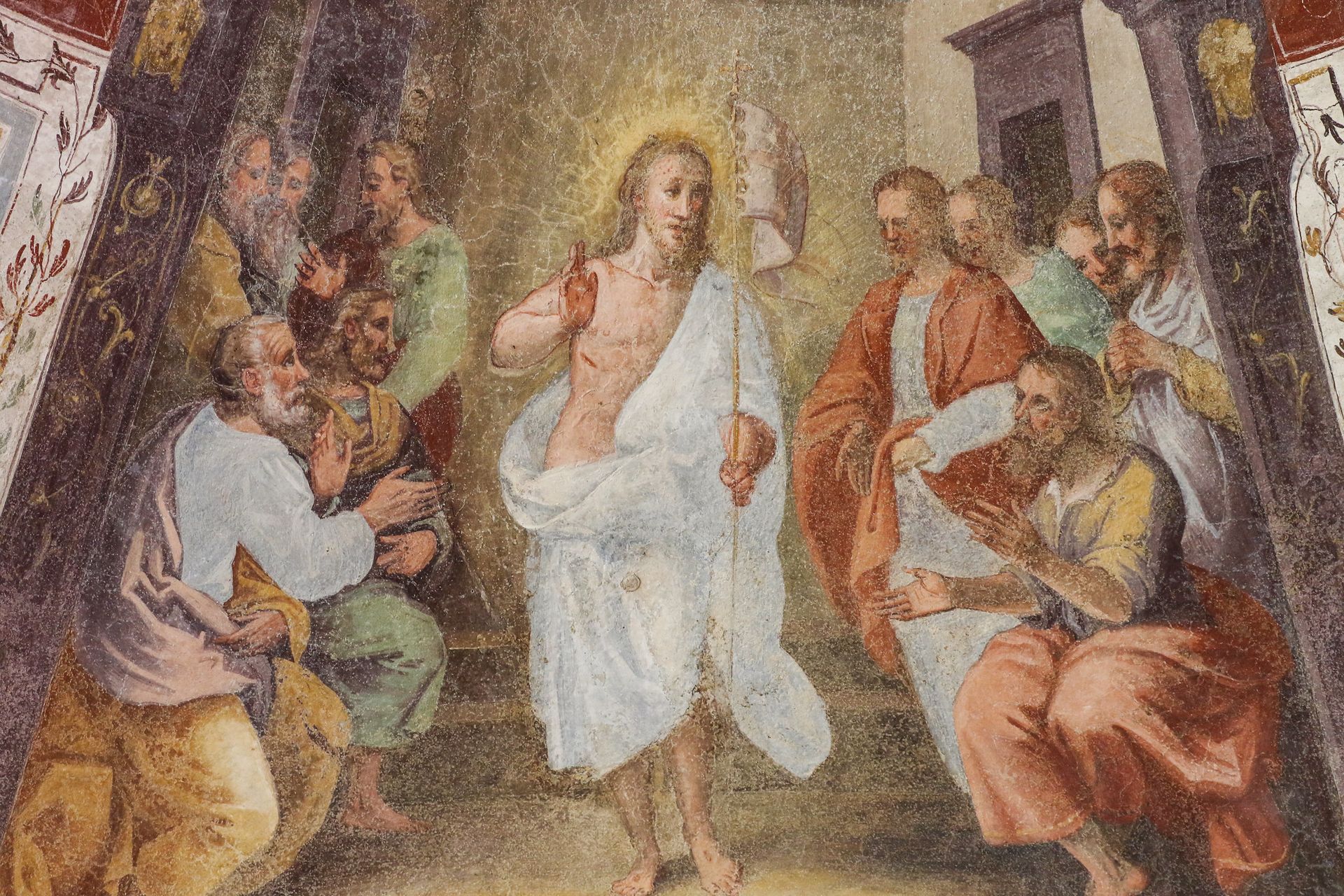

So, this Advent, we contemplate death: Our death, but even more so that of our Lord, whose death gives new meaning and new hope to our own death. The cross is always for us a symbol of hope, because it is that instrument by which the Son of God finished his work, humbling himself and becoming like us even in death, in order to overcome death on our behalf and open the way of everlasting life to all who trust in him.

It’s okay to feel a little blue in Advent. Because, as St. Paul says, we do not mourn as those who have no hope. We have the best hope of all in Jesus, who we know is coming to save us all from the dominion of sin and death, and bring us into his kingdom of light and life. What time is it? It is time to wake up and prepare to meet the Lord, sober and ready for his kingdom.