Advent Series: Heaven

The Third part in an Advent series on the “Four Last Things”

In one episode of the long-running animated sitcom The Simpsons Bart Simpson and his father Homer convert to Roman Catholicism, lured by pancake suppers, bingo, and the forgiveness of sins. This bothers Homer’s wife Marge, who doesn’t want to accept the Church’s teachings on birth control.

Marge imagines the afterlife. She arrives in “Protestant heaven,” only to see Homer and Bart on a nearby cloud in “Catholic heaven.” Compared to the genteel croquet-party vibe of Protestant heaven, Catholic heaven looks like it knows how to party. Marge asks to speak to Jesus about this, but it turns out that he’s also in Catholic heaven.

This depiction of “heaven” in The Simpsons is a reflection of its characters’ subconscious desires and anxieties, rather than an actual place. In reality, we don’t get a heaven tailored to our preferences. But The Simpsons may prompt us to ask the question, “what sort of ‘heaven’ would I be suited for? In what sort of ‘heaven’ would I feel at home?”

After asking this question we have to compare our subjective ideal of heaven with what we are actually told about heaven in scripture. After this, we can ask the question, “how would I need to change my life or adjust my expectations in order to be the kind of person who can look forward to heaven, as it really is, with confidence and hope?”

Scripture speaks of heaven in a number of places—often in symbols and metaphors. Heaven as it is is hard to describe. It is an eternal place, the place where God’s glory dwells. But a lot of the visions of heaven described in the Bible refer to the “new heavens and the new earth,” a renewed creation in which God dwells with his people.

Last week we heard Isaiah’s description of a new Jerusalem, which is part of this heaven. Today we view, perhaps not heaven itself but the road that leads to Jerusalem through the eastern wilderness of Judea. In Isaiah’s day (and in ours) it is a rough and dangerous road, contested by many powers, desolate and forbidding. This road and the country through which it passes are transformed in Isaiah’s vision. The desert blooms, and water fills it so abundantly that it is a wasteland no longer; it is a wetland, a place for birds and wildlife. Similar visions appear in the prophet Ezekiel as well as in Revelation; we find that there are both fresh and saltwater bodies of water in this area. Imagine the sound of flowing water, birds of all kinds, abundant wildlife.

This is the way of salvation, the road on which God will bring his exiled children home.

The dangers of the wilderness—animal and human—are no longer present. There are no predators, no bandits. In place of the rough road, an elevated highway, smooth and safe, with wide banks on both sides, leads to the holy city.

What kind of people are there?

In Isaiah’s vision, heaven is a place where losers become winners: “no traveler, not even fools, shall go astray.” The disabled are made whole: “The eyes of the blind shall be opened, and the ears of the deaf unstopped; then the lame shall leap like a deer, and the tongue of the speechless sing for joy.” The weak, the feeble, the oppressed will be strengthened, vindicated, and delivered from their oppressors. “Say to those who are of a fearful heart, ‘Be strong, do not fear! Here is your God. He will come with vengeance, with terrible recompense. He will come and save you.’“‘ It is a place for people who have learned patience in suffering.

This suffering may not have been undeserved. The disabilities mentioned—blindness, deafness, lameness, dumbness—are all characteristic of the way the Assyrians would mutilate conquered peoples. They are signs of defeat, of shame. In the spiritual interpretation of this passage, these are the wounds inflicted on God’s people by their sins. But now, they have been not only liberated from the bondage of sin, but even the effects and consequences of sin are being healed.

The highway to heaven is for those who have been made worthy; healed, cleansed, prepared for the presence of God. Isaiah’s vision of heaven is radically inclusive, admitting, in the words of the prayer book, people of “all sorts and conditions.” However, it also excludes those who persist in wickedness. “The unclean shall not travel on it, but it shall be for God’s people.” The Psalmist expands on this, “The Lord loves the righteous; the Lord cares for the stranger; he sustains the orphan and widow, but frustrates the way of the wicked.”

And it’s pretty clear that the wicked are not banging on the gates of heaven demanding to be let in. Isaiah’s heaven is not the sort of place that appeals to them.

This is because heaven is the place where God is. The humble, the poor, the oppressed, have come to know God as their helper and deliverer. God remains, for the wicked, their enemy. He is the one who continues to condemn their unjust intentions and frustrate their evil plans. His appearance throws them into confusion and they flee into darkness before the avenging sword of his mouth. They find themselves in a hell of their own furnishing, one that corresponds with who they truly are, with what they truly desire. But that’s a subject for another time.

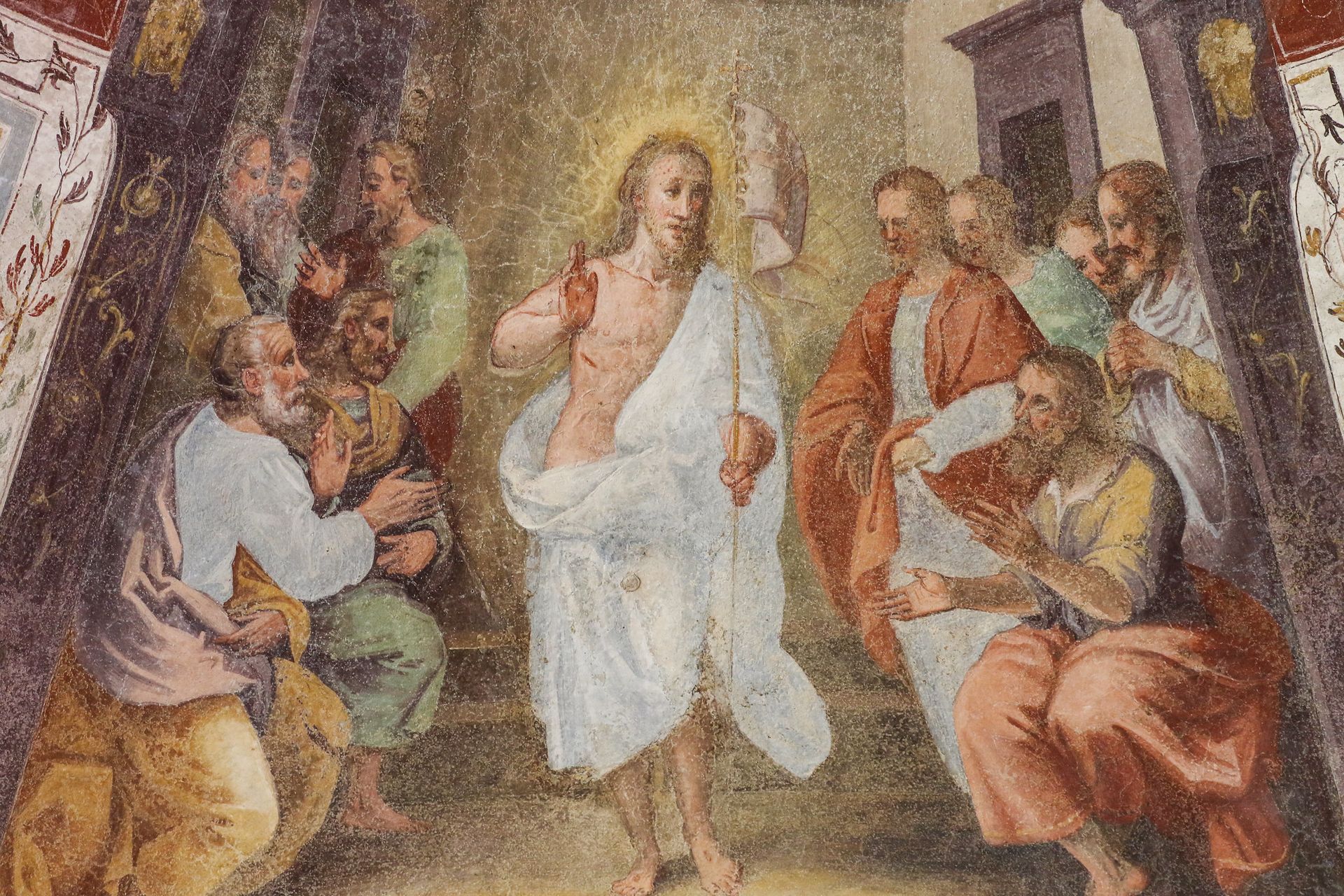

Jesus is called “the desire of the nations.” Though he “frustrates the wicked” and “puts down all the rulers of the earth” for their wickedness, Christ also awakens within the nations a desire for himself and for his holy place. At the end of the Bible there is a vision of this prophecy fulfilled, as not only the exiles of Israel but people from all nations stream into the new Jerusalem.

Jesus will be at the center of this heavenly city. It is the place where he will dwell with his people. So the question becomes, is Jesus the one for me? Is he the answer to my own longing?

Matthew’s Gospel relates this curious story about John, imprisoned by Herod, sending his disciples to question Jesus about his mission. Is he the promised messiah, anointed one, deliverer, or are they to wait for someone else?

Jesus responds by showing how his ministry fulfills—in very literal terms—the promises of the prophets. “Go and shew John again those things which ye do hear and see: The blind receive their sight, and the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, and the deaf hear, the dead are raised up, and the poor have the gospel preached to them.” And he adds, “And blessed is anyone who is not offended at me.”

I don’t think that John really doubts that Jesus is the one. It was he who identified him as the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world. It was John who said, “he must increase, but I must decrease” and sent his own disciples to follow Jesus. On the other hand, consider John’s circumstances at the time, unjustly imprisoned by an evil king for preaching against the king’s personal life. Any one of us in that circumstance might well wonder when Jesus intended to start making things right in the world.

Jesus has high praise for John as well. He calls him the greatest of all the prophets. And yet he says, “the least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he.” What Jesus is about to do is so much greater that it will put everything and everyone who came before him quite in the shade. The words of the prophets are fulfilled in no one else but Jesus himself.