Praying for the Dead

Homily at the St. Michael’s Requiem Mass for All Souls, November 2, 2022

As some of you know, I grew up in an evangelical context. And while that was good for me in many ways—particularly in teaching me the importance of a lively and personal relationship with Jesus Christ as my Lord and Savior, and giving me a respect for the Scriptures as the inspired and infallible word of God—it also contributed certain other habits of mind which I have had to unlearn.

For one thing, one of the assumptions I used to have was that one of the reasons I came to church was to learn, or to put it more accurately, to hear something new that would change my perception in some way. Whereas what we actually do in church is to hear things that are old; things that we already know; things that we have heard before, but have not yet completed their work within us. More than that, we come to encounter Jesus in the scriptures, in the sacraments, and in the fellowship of the congregation.

But even that account leaves out one of the most important aspects of corporate worship: prayer. We come to pray, which does not directly do anything. We make our requests, but it is up to God to fulfill them. We offer praise, but to a God whose all-sufficiency means that he does not actually need anything from us, not even words of affirmation. Even our greatest prayer, the one that is most central to our worship, which we call the Eucharist, the great thanksgiving, or the Mass, does not do or cause anything directly in itself. It is a petition, a commemoration, a request that, through our feeble human and earthly means, God will give us the grace that we need. The sacraments are powerful because they come with a promise, that if we use them, God will offer us what he promises through them. Or in other words, while God is present and active everywhere at all times, we know for certain that in the sacrament of the Altar he is present to us in a particular way, just as in baptism we have the assurance of forgiveness and being born again.

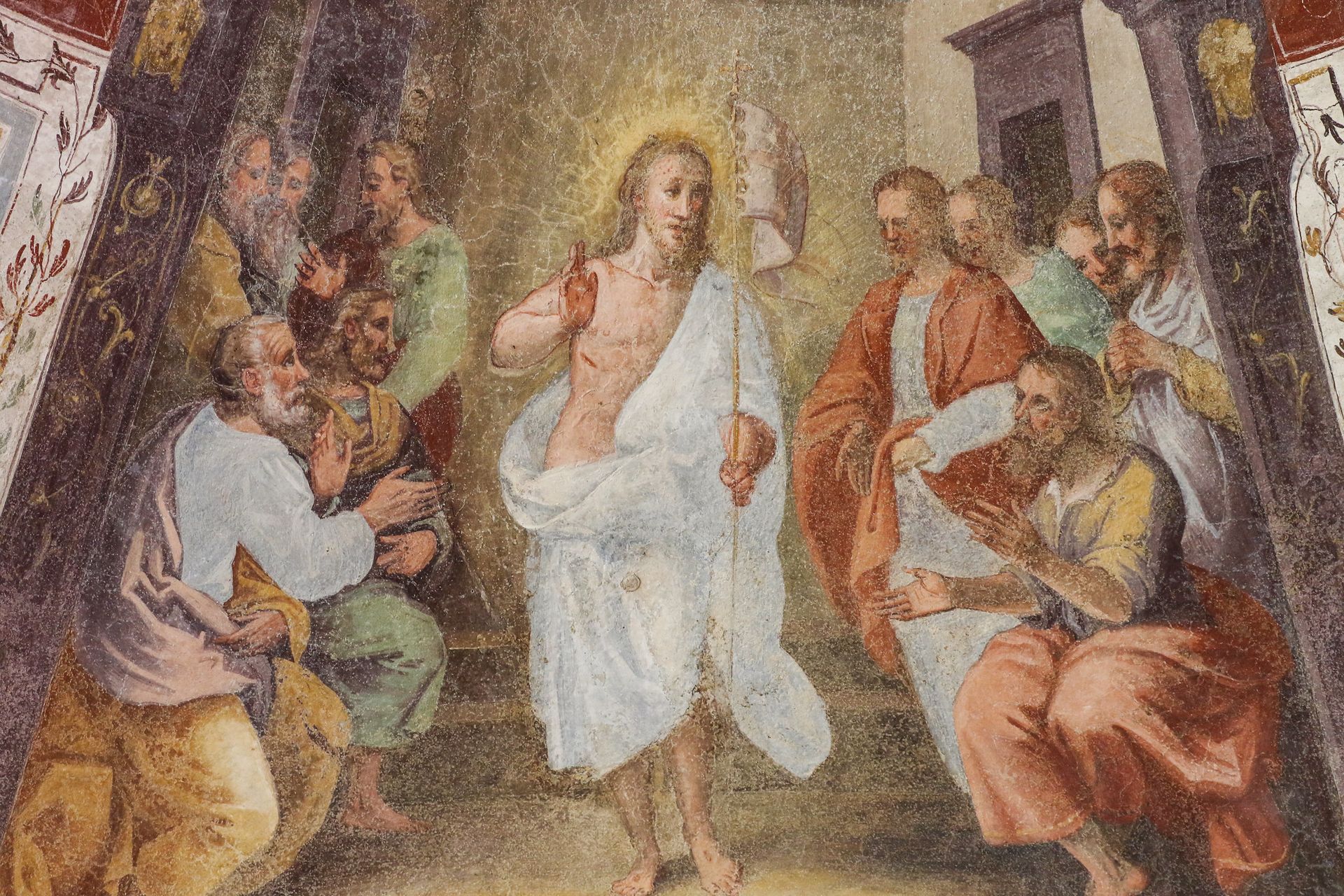

What does this all have to do with All Souls' Day? Well, in the Eucharist we do not so much offer up a new prayer to God, as enter into a worship event which is already and eternally taking place. We join the angels, and for a moment are lifted spiritually into the holy and heavenly places. It is a foretaste of what is to come. But we believe that those who have died in faith—the "faithful departed"—are already there in the presence of God. Ordinarily they are not present to us. Their souls have left this world, and only what was mortal of them has been left behind. (This includes, of course, their bodily remains, but also perhaps their memory and influence. Who of us can hope to be remembered two hundred years hence, except as, perhaps, a name on someone's family tree, a story passed down, an official record somewhere? How little I remember even of my own grandparents!)

The promise of All Souls is that there is one who does remember, and whose remembering is not limited to sentiment or the recollection of past events, but is strong enough to hold the reality of those who have departed this life in the power of his own life. Thus the dead are said to "rest," but they do not cease to exist, because they are known of God, and in the resurrection they will be fully restored; not merely to what they were on earth—transient, frail, and fallen—but to their fullest potential as created beings who share the divine gift of eternal life.

Now, as a young evangelical I was taught and firmly believed in the persistence of our souls after death, in the reality of heaven and hell, and in the hope of the resurrection, just as I preach today. But I was also taught to view "prayers for the dead" as a superstition, incompatible with the supposedly biblical understanding that after a person dies their fate is fixed, and they go immediately to heaven or hell. I am not sure now that scripture is all that clear about the immediate fate of the dead, or whether they are in need of our prayers. It is a matter of some controversy, and I don't think we can settle it today. But what we can do is to reflect on the communion of the saints. If we believe in the communion of all the saints, those who are made holy by Christ, both in this world and in the world to come, then we continue to be bound to those who have died, insofar as we all, living or dead, participate in Christ. Just as in the Eucharist we pray "by him, and with him, and in him," both our own spiritual life and the life of those who have died is by Christ, and with Christ, and in Christ. We offer our prayers through Christ, and they are answered according to the merits of Christ, not our own worthiness.

So when we pray for the dead, we do not do it because we think that every prayer of ours grants them some amount of time out of purgatory, or some such thing. We pray for them because we know that, wherever they are, God's will for them is the same as his will for us: that they would grow in the knowledge and love of God, to be more fully conformed to his image and attuned to his love. And we pray that we too might persevere in faith, so that at the resurrection, when the dead in Christ are raised, we also will be among them, united forever, through Christ, in the eternal life and love of God.